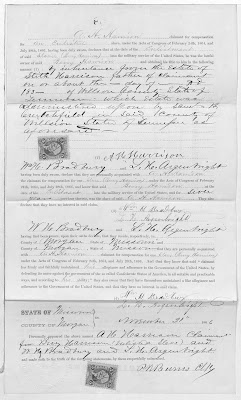

Signature from application for Presidential Pardon for James Davis after the Civil War.

Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Seth Manes (often noted as Seth II) was born in 1814 to Jacob Wilson Manes and Mary Lawson Manes six miles from Rogersville on the north side of Clinch Mountain in Hawkins County, Tennessee. Jacob was an Indian trader and fur trapper and was frequently gone from home. He had been kidnapped at age 11 and wasn't able to return for eight years. Although Jacob didn't have the chance for an education, he was known for his fantastic memory, especially for Bible verses. The Manes and Lawson families were Baptists. Seth and his brother Callaway became Baptist ministers.

Some sources state that the family moved to Indiana circa 1821. "Jacob Wilson Manes and Mary "Polly" Lawson Manes moved to a spot near Terre Haute, Indiana. Jacob, his wife and their six sons, Callaway, Wade, Seth, William Bryson, James and Nicholas, headed north in a covered wagon, crossing the states of Tennessee and Kentucky. When they came to the Ohio River, camp was struck for several days while a raft was built. This raft carried the family across to the Indiana side. The march northward was continued until a place was found to suit Jacob's fancy. The site was near what is now Terre Haute, Indiana. Here a log cabin was erected." Four more children were born to this couple after coming to Indiana: Lottie, Jane, Jacob, and Mahala.

Their son Callaway returned to Tennessee, marrying Sarah "Sallie" Evans on July 7, 1828. According to the 1830 Census he was married and living with his wife and infant son in Hawkins County. The young family moved on to Indiana, as did his wife's family, Archibald and Mary Manes Evans, with their other six daughters.

The Jacob Wilson Manes family was on the move again in 1832. This journey, however, was of short duration, lasting only three days or so. They stopped at a space 35 miles east of Terre Haute, in Clay Township, Owen County, Indiana. Here, according to Jacob Wilson Manes, was an ideal spot. The land was high and dry. There were almost no settlers and plenty of game. An abundance of water was supplied by Raccoon Creek and White River, which ran close by and were filled with good edible fish; plenty of timber was available for building. The location offered everything that tended to make a pioneer's life easier one. A cabin was built a little more than a quarter of a mile west of the present site of the Braysville school house on the south side of the Braysville-Freedom pile road.

In Indiana Seth was hired to a man, Sammy Howe, and lived with him continuously for years, giving most of his wages to the support of his mother and younger siblings.

By February 1835, Jacob Wilson Manes had moved to an area that would become Richwoods Township, Miller County, Missouri. Mary Polly Lawson Manes and several of the children stayed in Indiana. One story relates that he had left Indiana with a drove of horses and no one knew what became of him; however, four of his sons came to Missouri over the next few years.

Missouri had been granted statehood in 1821. The Osage Indians ceded their traditional lands across Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma in the treaties of 1818 and 1825. Jacob acted as administrator for William Evan's estate in 1835 and married William's widow, Emaline Hice Evans. Callaway's wife, Sallie, was a niece of William and Emaline Hice Evans. This same year Seth married Rebecca "Becky" Evans, a sister of Sallie, in Indiana.

Missouri had been granted statehood in 1821. The Osage Indians ceded their traditional lands across Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma in the treaties of 1818 and 1825. Jacob acted as administrator for William Evan's estate in 1835 and married William's widow, Emaline Hice Evans. Callaway's wife, Sallie, was a niece of William and Emaline Hice Evans. This same year Seth married Rebecca "Becky" Evans, a sister of Sallie, in Indiana.

Seth and Becky's daughter Mary Anne "Polly" Manes was born on April 12, 1837, in Indiana. A second daughter, Ellen Elizabeth, was born in 1838.

Callaway witnessed a land sale for Jacob and Emaline Manes in Miller County in 1839. He chose to settle in neighboring Pulaski County, Missouri. "For some time Callaway lived in a cabin in what was known as Still House Hollow on the William Gillespie farm on the Gasconade River when that entire area was wilderness. Callaway Manes, William Gillespie, and Isaac Davis, made a crop there. The cabin was an old trapper's cabin without any door or window. At the same time, he laid the foundations of two cabins on Conn's Creek, but continued to cultivate land on the Gillespie place until he had cleared out a sufficient land of his own claim. In those early years, the foundation for a cabin was sufficient to hold a claim against subsequent comers." The ties between the Manes and Gillespie families can be traced back to Moore County, North Carolina. The Gillespie and Davis families had come to Missouri in 1829.

By the 1840 Census, Callaway and Sallie Manes were living in Pulaski County next to Seth and his family, and near the wives' parents, Archibald and Mary Evans with four other daughters. Six of the seven Evans' daughters remained in Pulaski County for the rest of their lives. Seth and Becky's son, Thomas Callaway, was born in Pulaski County in March 1840, and Callaway and Sallie's son, William Gillespie Manes, was born in October. "Seth was offered his choice of the two claims on which Callaway had laid foundations. Seth chose the one near the head of the stream and, in due time, erected a house of heavy hewn log timbers in which he lived the remainder of his life and where he reared his children and some of his grandchildren. The claims were on the Gasconade River, about five miles southeast of where Richland exists today.

By the 1840 Census, Callaway and Sallie Manes were living in Pulaski County next to Seth and his family, and near the wives' parents, Archibald and Mary Evans with four other daughters. Six of the seven Evans' daughters remained in Pulaski County for the rest of their lives. Seth and Becky's son, Thomas Callaway, was born in Pulaski County in March 1840, and Callaway and Sallie's son, William Gillespie Manes, was born in October. "Seth was offered his choice of the two claims on which Callaway had laid foundations. Seth chose the one near the head of the stream and, in due time, erected a house of heavy hewn log timbers in which he lived the remainder of his life and where he reared his children and some of his grandchildren. The claims were on the Gasconade River, about five miles southeast of where Richland exists today.

According to Seth's half-brother, Samuel Jasper Manes, who lived with the family at times: "Seth differed from most of the Manes family, all of whom were high strung, fractious people. Seth was high strung, feared nothing on earth, but was not fractious. I was about his house a great deal, lived there as my own home two years as one of the family, and I never seen him yet off his balance, never heard a cross word spoken to his wife nor one of his children, yet he chastised his children and occasionally punished them, but always seemed to be in a perfect good humor. To illustrate his way, I will relate one circumstance. His oldest boy Callaway (Thomas Callaway) and the rest of his boys got into some mischief, but Callaway seemed to be the leader and Seth got onto it and called Callaway up, asked him about it. Callaway tried to justify himself, but Seth said, 'tut, tut, tut. Callaway you are too big a boy to act that way. I will have to give you a whipping in the morning.' This was Sunday afternoon. He was smiling all the time and talking in a kind way. Callaway was about fourteen years old, so we all supposed that ended it and went on our way. Next morning, after breakfast, Seth called Callaway out and give him a genteel dressing. When he got through, he said, 'My son, I hate to have to punish you, but you must not do such things - and if I have to punish you again I will make it a little worse.' And all that time was seemingly in a perfect good humor. That was his style with his family, his neighbors, and his stock; never seemed to fret over anything. He was honest to a cent and his work was considered good, was a good neighbor and the best man in case of sickness or distress I ever saw. When a neighbor got sick or had bad luck he was the first man to be on the group or help and often sacrificed his own interests to help others."

In February 1844, Jacob Manes left Miller County to join his sons Callaway and Seth in Pulaski County. Jacob Wilson Manes cleared four acres of land that spring for William Gillespie in the lower field of the Jesse Gillespie Place. Jacob and his family moved on to Hot Springs, Arkansas, where his step-daughter, Minerva Jane Evans, married Reuben Lambert in 1850. In January 1853 Reuben Lambert and Jacob Wilson Manes got into a fight near Mountain Grove, Missouri, and Seth's father was killed. It's plausible that the two men were trapping and trading furs, as the fur-trading town of Astoria existed near Mountain Grove at that time.

Seth served as Justice of the Peace for 18 years. Additional children were born as follows: 1841 Francis Marion Manes, 1843 Jacob Newton Manes, 1845 Sarah Malinda, 1846 Simeon Henderson, 1848 John Aaron, 1849 Mahala Catherine, 1851 Daniel Lorenzo, 1852 Matilda Emmaline,

In 1848 their brother Wade joined them in Pulaski County. He stayed until 1855, moving on to Flat River where he died in 1864. His family moved on to Texas.

In August, 1851, Seth's mother, Mary Polly Lawson Manes, died in Owen County, Indiana. Although she used the name Manes, her children who stayed in Indiana used the name Maners.

Seth served as Justice of the Peace for 18 years. Additional children were born as follows: 1841 Francis Marion Manes, 1843 Jacob Newton Manes, 1845 Sarah Malinda, 1846 Simeon Henderson, 1848 John Aaron, 1849 Mahala Catherine, 1851 Daniel Lorenzo, 1852 Matilda Emmaline,

In 1848 their brother Wade joined them in Pulaski County. He stayed until 1855, moving on to Flat River where he died in 1864. His family moved on to Texas.

In August, 1851, Seth's mother, Mary Polly Lawson Manes, died in Owen County, Indiana. Although she used the name Manes, her children who stayed in Indiana used the name Maners.

In 1858 Seth and Becky's first daughter Mary Anne Polly Manes married George W. Vaught on May 11. George was born in Alabama in 1833. (1880 Census of Pulaski County) He homesteaded 160 acres near Dublin. He walked to North Missouri to record his deed. George said the 160 acres cost ten cents an acre. His home was a big log house with a lean-to and by that was another cabin which was used as a kitchen. Later he built a two-story, all the logs the same size, hewed and notched at the corners. The fireplace was on the east end. Big porches were on the north and south sides. This home was built near the spring. A log smokehouse was built and the cooking was done here in the summer.

In 1860 their oldest son Thomas Callaway married Nancy York and their daughter Ellen Elizabeth married William Elbert York.

Seth McCully Manes (III) was born in 1861.

In 1860 their oldest son Thomas Callaway married Nancy York and their daughter Ellen Elizabeth married William Elbert York.

Seth McCully Manes (III) was born in 1861.

The Manes Family of Preachers and Teachers